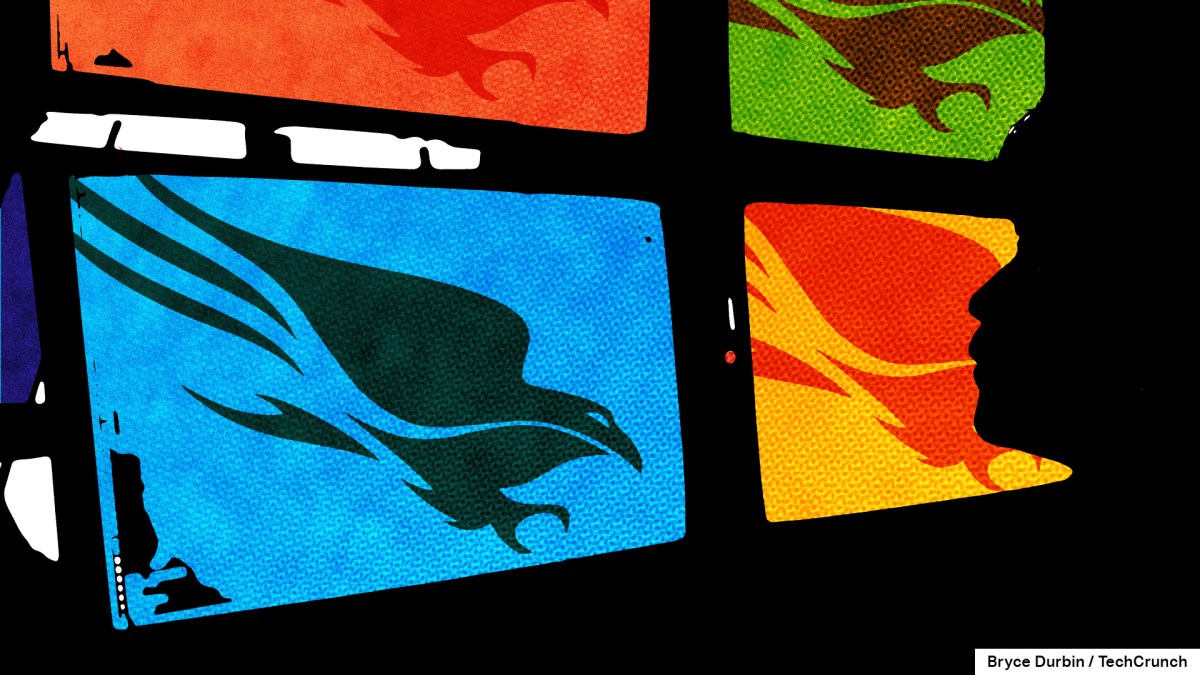

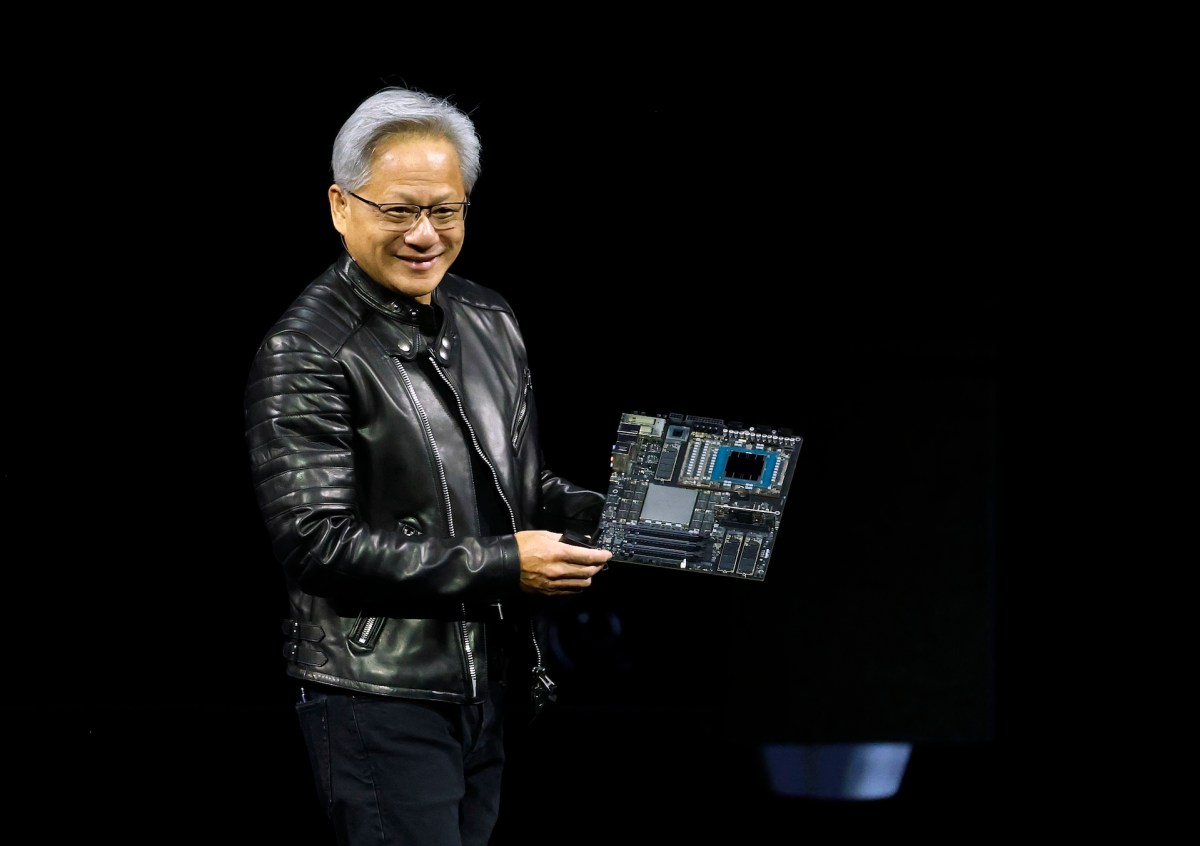

When Will Bruey talks about the future, the timelines are shorter than most might imagine. The Varda Space Industries CEO predicts that within 10 years, someone could stand at a landing site and watch multiple specialized spacecraft per night zooming toward Earth like shooting stars, each carrying pharmaceuticals manufactured in space. Within 15 to 20 years, he says, it will be cheaper to send a working-class human to orbit for a month than to keep them on Earth.

The reason Bruey thinks these scenarios are realistic is because he has watched ambitious business projections unfold before, while working as an engineer at SpaceX.

“I remember the first rocket I worked on at SpaceX was flight three of Falcon 9,” he said at TechCrunch’s recent Disrupt event. The partially reusable, two-stage, medium-lift launch vehicle has since completed nearly 600 successful missions. “If someone had told me ‘reusable rockets,’ and ‘[we’ll see as] many [of these] flights as daily flights out of LAX,’ I would have been like, ‘All right, [maybe in] 15 to 20 years,’ and this feels the same level of futuristic.”

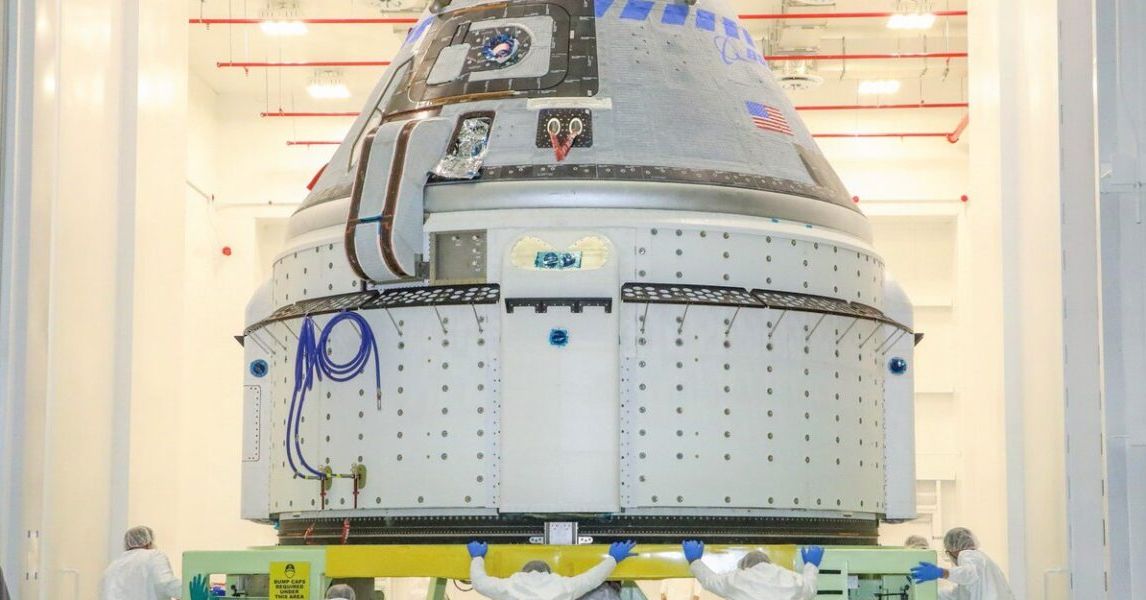

Varda has already proven the core concept. In February 2024, after a months-long regulatory odyssey, the company became only the third corporate entity ever to bring something back from orbit – crystals of ritonavir, an HIV medication – joining SpaceX and Boeing in that exclusive club. It has completed a handful of missions since.

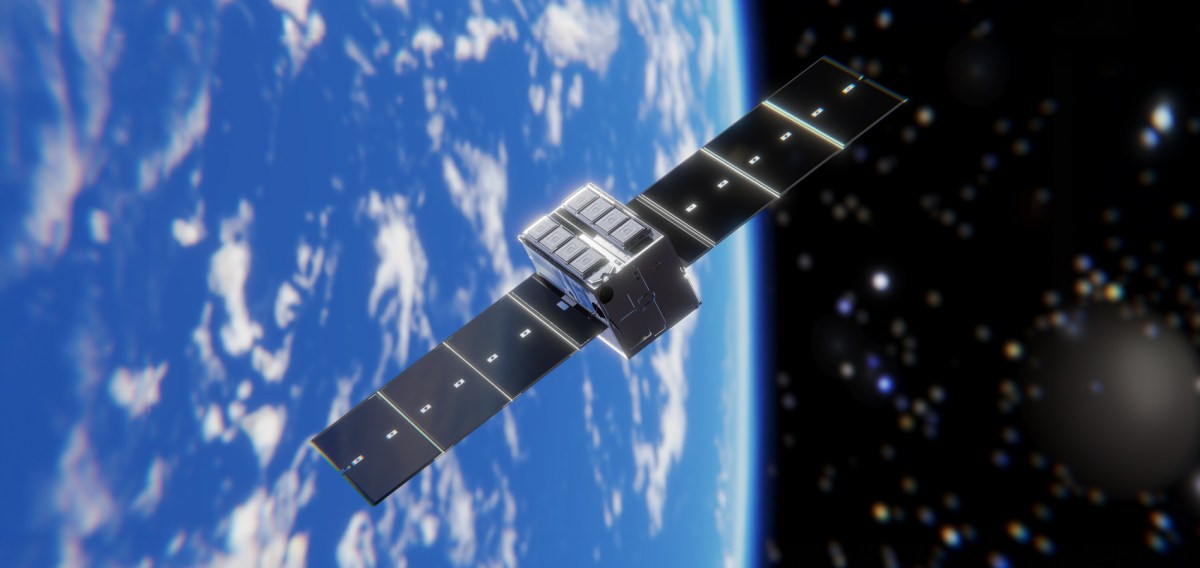

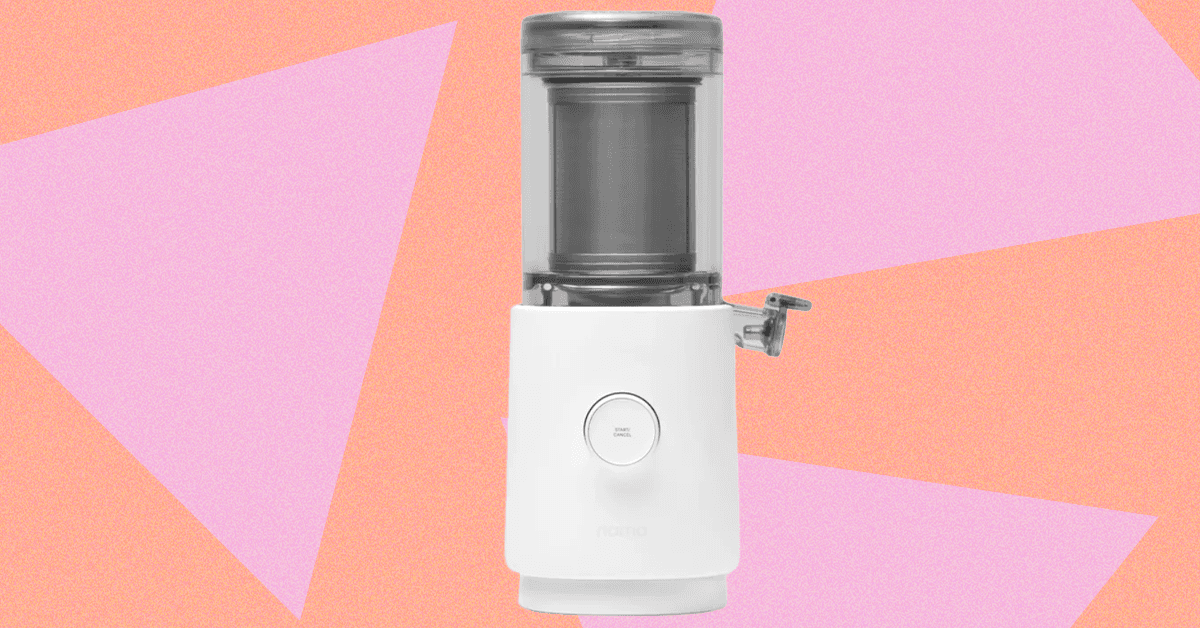

The company brings its pharmaceuticals back to Earth inside the W-1 capsule, a small, conical spacecraft about 90 centimeters across, 74 centimeters high, and weighing less than 90 kilograms (roughly the size of a large kitchen trash can). The company launches these capsules on an ad-hoc basis aboard SpaceX rideshare missions, where they’re hosted by a Rocket Lab spacecraft bus that provides power, communications, propulsion, and control while in orbit.

So why manufacture crystals in space? In microgravity, the usual forces that interfere with crystal formation on Earth – like sedimentation and gravity pulling on growing crystals – essentially disappear. Varda says that this gives it much more precise control over crystallization, allowing it to create crystals with uniform sizes or even novel polymorphs (different structural arrangements of the same molecule). These improvements can translate into real benefits: better stability, greater purity, and longer shelf life for drugs.

The process isn’t quick. Pharmaceutical manufacturing can take weeks or months in orbit. But once it’s complete, the capsule detaches from the spacecraft bus and plunges back through Earth’s atmosphere at over 30,000 kilometers per hour, reaching speeds above Mach 25. A heat shield made of NASA-developed carbon ablator material protects the cargo inside, and a parachute brings it down for a soft landing.

Techcrunch event

San Francisco

|

October 13-15, 2026

Bruey says people often get Varda wrong. The company isn’t “in the space industry; we’re in-space industry,” he said. Space is “just another place to ship to.”

Put another way, the actual business is pretty prosaic, he proposed, suggesting that people imagine a bioreactor, or just an oven, that has the usual knobs – temperature, stir rate, pressure – and offering that Varda is adding a “gravity knob.”

“Forget about space for a second,” said Bruey. “We just have this magic oven in the back of our warehouse where you can create formulations that you otherwise couldn’t.”

Worth noting: Varda isn’t discovering new drugs or creating new molecules. It’s aiming to expand the menu of what can be done with existing, approved drugs.

This isn’t speculative science. Companies like Bristol Myers Squibb and Merck have been running pharmaceutical crystallization experiments on the International Space Station for years, proving the concept works. Varda says it’s just making it commercial by building the infrastructure to do it repeatedly, reliably, and at a scale that might actually matter to the pharmaceutical industry.

As for why now, two things have changed. First, space launches have become bookable and predictable. “Ten years ago, you would have to get a chartered flight. It was like hitchhiking to get to orbit if you were not a primary mission payload,” Bruey explained. “It’s still expensive today, but [it’s dependable, you can book a slot, and we [have] booked launches years in advance.”

Second, companies like Rocket Lab started producing satellite buses that could be purchased off the shelf. Buying Photon buses from Rocket Lab and integrating its pharmaceutical manufacturing capsules with them was a major unlock.

Still, only the highest-value products make economic sense. That’s why Varda started with pharmaceuticals; a drug that can command thousands of dollars per dose can absorb the transportation costs.

The “seven domino” theory

When Bruey talks to members of Congress, which he says he does frequently these days, he pitches what he calls the “seven domino theory.”

Domino one: reusable rockets. Done. Domino two: manufacturing drugs in orbit and returning them. Domino three is the big one: getting a drug into clinical trials. “It’s a big deal because what it means is perpetual launch.”

This is where Varda’s business model diverges fundamentally from every other space company.

Think about how satellite companies work. SiriusXM launches satellites to broadcast radio. DirecTV launches satellites to transmit television. Even Starlink, with its thousands of satellites, is fundamentally building out a constellation – a network that, once complete, doesn’t require constant launches to function. These companies treat launch as a capital investment. They spend money to place hardware in orbit, and then they’re done.

Varda is different. Each drug formulation requires manufacturing runs. Manufacturing runs require launches. More demand for the drugs means more launches.

This matters because it changes the economics for launch providers. Instead of selling a fixed number of launches to build out a constellation, they have a customer with (theoretically) unlimited demand that grows with success. That kind of predictable, scalable demand helps justify the fixed costs of launch infrastructure and drives down per-launch prices.

Domino four triggers the feedback loop: as Varda scales, costs drop, making the next tier of drugs economically viable. More drugs mean more scale, lowering costs again – a cycle Bruey says will “shove launch costs into the ground.”

Varda’s commercial viability remains unproven, and no space-manufactured drugs are currently on pharmacy shelves. But the virtuous cycle Bruey imagines won’t just benefit Varda. Lower launch costs make space accessible for other industries, including semiconductors, fiber optics, and exotic materials – everything that benefits from microgravity but can’t yet justify the expense.

Eventually, Bruey tells his team, launch costs will get so low that it will be cheaper to put an employee in orbit for a month because creating additional automation would cost more.

“I imagine ‘Jane’ goes to space for a month. It’ll be like [heading to] an oil rig. She works at the drug factory for a month, comes back down, and [becomes] the first person ever to go to space and back where she generate[s] more value than the cost to take her there.”

It’s at that moment, Bruey says, when “the invisible hand of the free market economy lifts us off our home planet.”

The near-death experience

The path to those shooting star drug deliveries nearly ended before it began, Bruey told TechCrunch.

Varda launched W-1 in June 2023 aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rideshare mission. The pharmaceutical manufacturing process inside the capsule worked as planned, producing crystals of Form III ritonavir, a specific crystalline structure of the HIV drug that’s difficult to create on Earth. The experiments were completed within weeks.

But then the capsule just . . . stayed in orbit. For six months. The problem wasn’t technical, Bruey said; Varda couldn’t get approval to bring its W-1 capsule home.

The Utah Test and Training Range, where Varda wanted to land, exists to “test weapons and train warriors,” as Bruey put it. Space drugs didn’t fall into that category, so Varda wasn’t a priority customer. When higher-priority military missions needed the range, they bumped Varda’s scheduled landing windows. Each bump invalidated the company’s reentry license with the FAA, requiring it to start the approval process over.

“There were 80 people in the office who had spent two and a half years of their lives on this thing, and it’s in orbit, but we’re not sure if it can come home,” Bruey recalled.

The situation looked bad from the outside. To observers, it seemed like Varda had been reckless and launched without proper approvals. But he said in reality, the FAA had authorized Varda to launch without a finalized reentry license because the agency wanted to encourage the nascent commercial reentry industry.

The FAA had authorized Varda to launch without a finalized reentry license, encouraging the nascent commercial reentry industry.

“They encouraged us to proceed with our launch, with the goal being that we would continue to coordinate that license, as well as the use of reentry timing with the range, while we were in orbit,” Bruey explained.

The real problem was that this was the first commercial land reentry ever attempted. There was no established process for the Utah range to coordinate with the FAA. Both entities felt like they were shouldering all the liability.

Varda explored every alternative it could think of. Water landing? The capsule doesn’t float; they’d lose it. Australia? Possible, and they started those conversations. But Bruey says he made a call: no half measures.

“Either you have to push the boundaries of regulation to create this future, or you don’t,” he said. “In order for Varda to be successful, we need to land on land regularly. So we just sucked it up and said, ‘Let’s figure this one out.”

While its first mission remained stranded in orbit, the company continued production on the next capsule. It kept hiring.

In February 2024, eight months after launch, W-1 finally came home. It landed as originally planned at the Utah Test and Training Range, the first commercial spacecraft to land on a military test range and the first to land on U.S. soil under the FAA’s Part 450 licensing framework, introduced by the agency in 2021 to make commercial space operations more flexible.

Now Varda has landing sites in both the U.S. and Australia, and it’s the first company to receive an FAA Part 450 operator license that lets it reenter the U.S. without resubmitting full safety documentation for each flight.

Meanwhile, Varda has a secondary business that emerged from necessity: hypersonic testing.

Very few objects ever travel through the atmosphere at Mach 25. The environment at those speeds is extreme and unique: Temperatures reach thousands of degrees, creating a plasma sheath around a vehicle. The air itself undergoes chemical reactions as molecules are ripped apart and recombine. This environment can’t be replicated on Earth, even in the most advanced wind tunnels.

The Air Force and other defense agencies need to test materials, sensors, navigation systems, and communications equipment in real hypersonic conditions. Traditionally, that would require dedicated test flights that cost upwards of $100 million each and involve significant risk.

Varda offers an alternative. Its W-1 capsules are already reentering at Mach 25. The company can embed sensors, test new thermal protection materials, or validate equipment in the actual flight environment rather than in approximations. The capsule is akin to a wind tunnel, and the reentry is the test.

Varda has already flown experiments for the Air Force Research Laboratory, including an optical emission spectroscopy payload that took in-situ measurements of the shock layer during reentry.

Investors are, big surprise, excited about Varda’s story. The company raised $329 million as of its Series C round this past July, most of it earmarked for building out the company’s pharmaceutical lab in El Segundo. It’s also hiring structural biologists and crystallization scientists to work on more complex molecules, eventually including biologics like monoclonal antibodies, which Bruey says is a $210 billion market.

A whole lot has to go right between then and now for Varda to elbow its way into that business, as well as to make a dent in the business it’s currently targeting. But if Bruey is right, “then” is closer than most people might right now imagine.